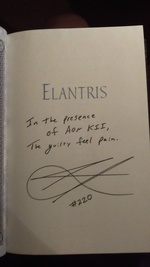

Brandon Sanderson

Chapter Forty-One

My biggest challenge in this chapter was to make it believable to a reader that the characters would accept Sarene as an Elantrian. The plotting of this section of the book relies on Sarene thinking that she's actually been transformed–otherwise, she would try to escape, and I wouldn't be able to have the short interlude in Elantris I have here. It's vital to Raoden's plotting, and to the relationship between the two of them, that they have some time to think and to get to know one another.

I had a couple things going for me in creating this suspension of disbelief regarding Sarene's nature as an Elantrian. First, she doesn't really know what an Elantrian should be like–she doesn't realize that her heartbeat or her tears betray her. Secondly, as Raoden will point out in a bit, Sarene has come during the time of New Elantris. There is food, there is shelter, and the pain has mostly been overcome. The differences between an Elantrian and a non-Elantrian, then, are less obvious.

Even still, there are a couple of things I had to explain. The first is Ashe's existence. This is a major clue to Sarene and company that she's not really an Elantrian. Sarene's bodily changes–or lack thereof–are going to be more and more obvious the longer she stays in Elantris. Obviously, I wouldn't be able to pull this plotting off for very long, but hopefully it works for now.